After enduring a painful injury from a snare for over two years, a wild bull elephant in Zimbabwe has been freed by a dedicated team of veterinarians and conservationists.

Spotted near Zambia’s border two years ago by the Wildlife Conflict Management Chirundu Elephant Program, this 35-year-old elephant’s initial rescue attempt was thwarted when he disappeared before aid could reach him.

Fast forward to last month, he reappeared in the company of three other elephants during lunchtime, a sight confirmed by Lisa Marabini of AWARE Trust, a veterinary-led wildlife conservation organization.

Despite his newfound companions, he exhibited signs of continued distress. A visible leg injury caused by a snare and circular skin patches hinting at infection signaled his health was declining.

The snare, resulting from widespread poaching due to Zimbabwe’s high unemployment rate and poverty, must be removed urgently.

To rescue the elephant, Marabini and her colleague, Keith Dutlow, embarked on a 500-mile journey.

In Zimbabwe, snares are a common peril for wildlife, from antelopes to lions, rhinos, and elephants. If trapped, elephants often break free, but not without the wire causing long-term damage, leading to conditions like osteitis, inflammation of the bone.

Locating the elephant was only half the battle. Successfully darting him to sedate the animal presented another challenge.

Following an intense 45-minute pursuit, the veterinarians could finally dart the elephant. Despite the associated risks – the sedative could compromise the elephant’s ability to breathe or damage his nerves – the operation was successful.

The snare removal was far from straightforward, with the depth of the wound requiring expanded incisions. As daylight dwindled, the task became more daunting.

However, refusing to admit defeat, the veterinarians continued their efforts under the dim light of the Land Rover’s headlights and cell phones.

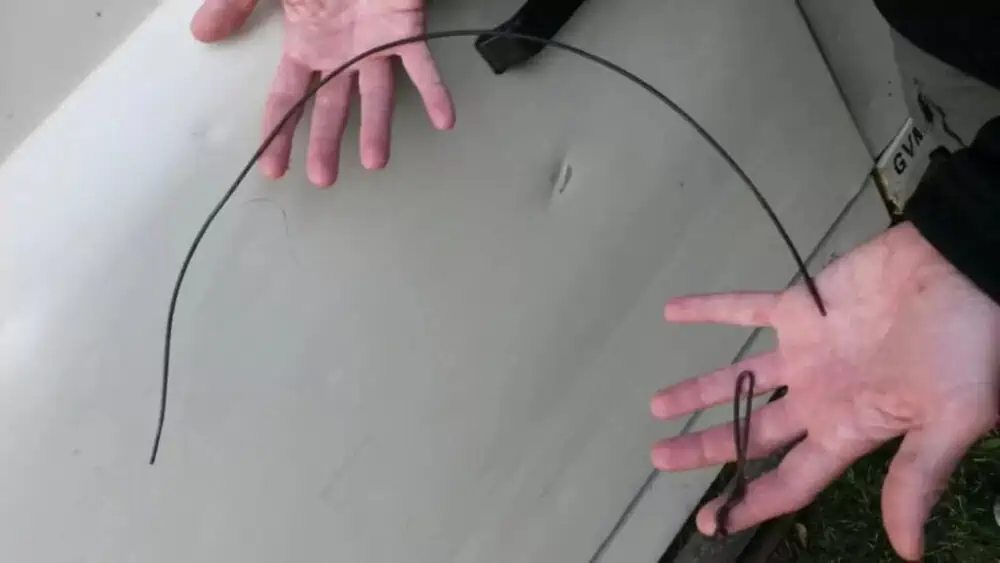

Finally, they managed to extract the wire from the wound. The moment was met with overwhelming joy, making the stress worthwhile.

The elephant was then treated with antibiotics, and the sedative was reversed. Although cloaked in pitch darkness, the team could discern the outline of the elephant as he rose to his feet.

Not all elephants in Zimbabwe share this lucky outcome. Just last month, an attempt to treat another elephant failed due to complications.

This elephant, victim to the ivory trade, bore an AK-47 bullet hole in his cheek and trunk. Marabini ends solemnly, stating that “EVERY elephant life now counts.”